Sheer luck is as good as past returns in predicting future performance

The big investment shift of recent years is from active to passive. Clients have been buying index funds, which passively track a benchmark like the S&P 500 index, and shunning fund managers who actively try to pick the best shares.

One reason for the shift is that passive managers charge lower fees than active funds. Many clients would be happy to pay more if that translated into better performance. However, it is very difficult for investors to select fund managers who can reliably beat their peers. Performance does not persist, as the latest data from S&P Dow Jones Indices show clearly.

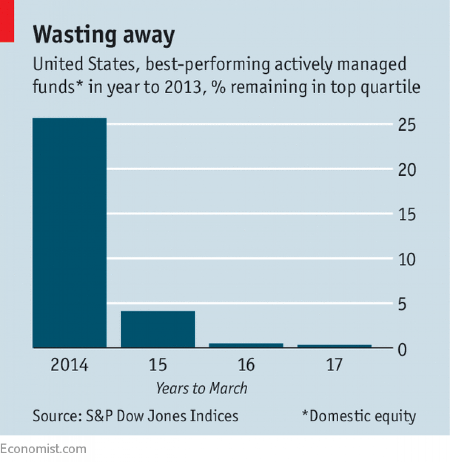

Suppose you had picked one of the best-performing 25% of American equity mutual funds in the 12 months to March 2013. In the subsequent 12 months, to March 2014, only 25.6% of those funds stayed in the top quartile (see chart). That result is no better than chance. In the subsequent 12-month periods, this elite bunch is winnowed down to 4.1%, 0.5% and 0.3%—all figures that are worse than chance would predict. Similar results apply if you had picked one of the best-performing 50% of all funds; those in the upper half of the charts failed to stay there.

Suppose you had picked one of the best-performing 25% of American equity mutual funds in the 12 months to March 2013. In the subsequent 12 months, to March 2014, only 25.6% of those funds stayed in the top quartile (see chart). That result is no better than chance. In the subsequent 12-month periods, this elite bunch is winnowed down to 4.1%, 0.5% and 0.3%—all figures that are worse than chance would predict. Similar results apply if you had picked one of the best-performing 50% of all funds; those in the upper half of the charts failed to stay there.

Perhaps this is an unfair comparison; fund managers cannot be expected to outperform every year. But clients do hope they can deliver superior returns over the long run. So S&P Dow Jones Indices ran the numbers in a different way. Suppose you had picked a fund with a top-quartile performance in the five years to March 2012. What proportion of those funds would be in the top quartile over the subsequent five years (to March 2017)?

The answer is just 22.4%: again, less than chance would suggest. Indeed, 27.6% of the star funds in the five years to March 2012 were in the worst-performing quartile in the five years to March 2017. Investors had a higher chance of picking a dud than a winner.

The industry’s answer to this problem is to launch a lot of funds. Some of them are bound to be near the top of the charts and can be trumpeted in adverts; the losers can then be killed off. Almost 30% of the worst-performing (bottom quartile) equity funds over the five years to March 2012 had been merged or liquidated by March 2017.

It should not be a surprise that the average fund fails to beat the index. The “iron law of costs” is that, in aggregate, professional fund managers own most of the stockmarket. Thus their performance is highly likely to resemble that of an index that tracks the overall market. But the index does not incur costs or fees; fund managers do. Thus the average fund manager must underperform the market, after costs.

Why doesn’t fund management conform to the rules of professional sports, where athletes such as Cristiano Ronaldo or Roger Federer consistently outperform their rivals? One reason could be that successful managers attract more clients, and the size of their fund grows.

So they have to expand the number of stocks they buy, diluting their best ideas. As the fund grows larger, it looks more like the overall market, and runs into the iron law of costs.

A second possibility is that active managers tend to have a “style”, favouring particular types of shares. One style is the value approach, whereby investors seek shares that look cheap compared with a company’s profits, assets or dividend payments. But styles can go in and out of fashion as relative valuations change; value stocks can outperform for a while and then slump. So managers who follow that style will beat their peers for a period and then drop to the back of the pack.

The final possibility is that outperformance (or underperformance) is simply the result of luck. Picking shares is enormously difficult, given all the potential factors involved. In the American stockmarket thousands of funds pore over the same information. It is very hard for an individual investor to get an edge.

Active fund management may have more of a role to play in other places: emerging markets, for example, where information about the prospects of individual companies is not so widely available; or bond funds, where S&P did find some evidence of persistent performance in areas such as mortgage-backed securities, municipal debt and investment-grade debt. In such areas, specialist knowledge may prove an advantage.

But when it comes to American equities, it is a different story. The average fund manager runs a portfolio for only around four-and-a-half years. So if you pick a fund based on its record, the chances are that a new person is in charge. The old saying that “past performance is no guide to the future” is not a piece of compliance jargon. It is the truth.

Economist.com/blogs/buttonwood

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline “The past is a foreign country”